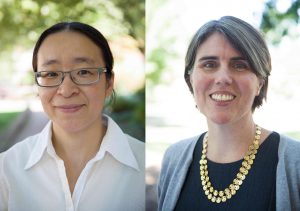

Hosts Jonathan Weiler and Matthew Andrews welcome Yan Song, professor of city and regional planning and director of UNC’s Program on Chinese Cities; and Noreen McDonald, chair of the department of city and regional planning and director of the Carolina Transportation Program.

Transcript

Matthew Andrews: Welcome back, everyone. This is the “COVID Conversations” podcast produced by the College of Arts & Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We are pleased to have been invited back to do this again, semi-shocked, I think that we have been asked back, frankly. My name is Matt Andrews. I am a professor in the Department of History here at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Jonathan Weiler: And I’m Jonathan Weiler, a professor in global studies at UNC-Chapel Hill.

MA: First of all, Jonathan and I sincerely hope that you are all doing well. We hope for your health and your sanity, that you’re finding moments of joy in these strange and discomforting times. Speaking of joy, Jonathan and I have been known to occasionally record a different podcast called “The Agony of Defeat”, which consists essentially of our ramblings about the intersection of sports, history, and politics. You can find it on iTunes and we hope to record more episodes of that podcast shortly. But in the meantime, we are honored to have been asked and given the opportunity to sit down and talk with some of our colleagues here at UNC and get their thoughts on the COVID-19 pandemic and hear their insights and expertise from the perspective of their particular fields. Last week, it was our pleasure to speak with Paul Delamater in the geography department. Paul had so many interesting things to say. So thank you once again, Paul. This week we’ll be speaking with two colleagues in the Department of City and Regional Planning. We will be talking in general about the perils and the promises of cities and urban infrastructures in our current COVID moment, and also looking forward a little bit. But first, very quickly, Jonathan, you and I are sports guys. Well, we like to think we are so much more but we are drawn to the world of sports. We are recording this podcast on the afternoon of April 16th. Now as I know you know, yesterday, April 15th, was Jackie Robinson Day. The 73rd anniversary of Jackie Robinson desegregating Major League Baseball in 1947. Maybe the single most significant moment in the history of American sports. So I have a question for you: do you know what today is, April 16th?

JW: I do not, Matt.

MA: All right, I’m going to educate you here, Jonathan. Today is National High Five Day.

JW: Okay.

MA: The day you put your un-gloved, un-sanitized hand high up in the air and you ask everyone with your un-masked lips to “give me five”. Not a good idea at this particular moment. As of this moment, is the high five; is it a cultural relic, the high five?

JW: I was gonna [sic] say Matt, it might be that the high five is going to go the way of the handshake after this is all said and done.

MA: So you’re saying we will never high five again?

JW: Certainly not in an un-gloved fashion, I would think.

MA: Well okay, Jonathan and I would like to give a virtual high five to our guests today. Let me introduce them one at a time. Dr. Yan Song is a professor in the UNC Department of City and Regional Planning and also the Director of the UNC Program on Chinese Cities. This is a program that seeks to better understand the impacts of rapid urban growth on Chinese built and natural environments and it explores ways to make urbanization more equitable, more transparent, and more ecologically sustainable. Dr. Song’s research, broadly speaking, explores sustainable and smart cities, and I’m hoping to get a better sense of what a smart city is in our conversation today. Yan joins us in socially-distant fashion, of course, from her home in Chapel Hill. Yan, thank you so much for joining us today.

Dr. Yan Song: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

MA: And also with us today is Dr. Noreen McDonald. Dr. McDonald is the Chair of the Department of City and Regional Planning, as well as the Director of the Carolina Transportation Program. The Carolina Transportation Program brings together researchers from across the UNC campus who are interested in, well, transportation obviously. Scholars and students aligned with this center might have a primary interest in air quality modeling or maternal and fetal health, many different areas, but their work all touches on transportation in some way. Dr. McDonald’s research explores how investments in infrastructure, such as roads and bike lanes, how they influence everything from travel decisions, to public health, to the actual shape of our cities. Noreen also joins us in socially-distant fashion from her home in Carrboro. Noreen, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us today.

Dr. Noreen McDonald: Nice to be here.

MA: And Noreen, in all seriousness, when are we going to get more bike lanes in Chapel Hill? Can I rely on you to get that done?

NM: They’re working on it.

MA: Can I send all my complaints to you? Is that okay?

NM: Yes, of course, all of them.

MA: I appreciate that. Okay, Yan, let’s start with you. This virus began in a Chinese city and please note that I’m not calling it a Chinese virus. But the fact is, it began in Wuhan. Can you please start us off just by speaking about what it is about a city like Wuhan that made it possible for this virus to originate and get a foothold and spread, or could it have been in any city or in any place?

YS: Right. Sure, so Wuhan is a very dense city with more than 8 million people living there or working there, and it’s also a city with lots of universities. It’s one of the cities in China with the most, with the highest number of college students, right. So this virus, it’s believed nowadays, that it probably began in late December last year or early January, probably most likely late December in 2019. And then, the sort of first two weeks I will say, there was nothing because people had no knowledge of this virus. It’s new and in sort of a harmful way. So nobody knew that, of course, nobody knew at the time this could happen and to make things worse, in January, late January is the Spring Festival of China. And typically in Spring Festival, people move back to their hometowns. And I just mentioned that Wuhan is the city with lots of college students, right, and they are all moving back from Wuhan to all corners in China. So basically, to January, I checked on the number, to January 23, nothing has been done, again, simply because of lack of knowledge, right. And at the same time, just before January 23, there was this massive migration in the country or even internationally, because people were taking off holidays, they were traveling overseas for tourism, possibly, as well. So, before the 23 of January, there wasn’t any interventions going on. But then, on January the 20 people there, professionals there, realized that this is a serious thing, right, and that this virus could or was capable of human-to-human transmission. So on the 23rd, the officials announced that it’s a total lockdown of the city. Nobody can go in or outside of the city of Wuhan and all the traffic has been suspended. You know, all the public transits [sic], inter-city or intra-city traffic has all been suspended. And there was this strict rule in terms of home quarantine, right. So in this case, people were not allowed to go outside their homes and their houses, their apartments, there was this really strict home quarantine, right. And this time, so the earlier failure here is that of course there’s a slow response. And when there were almost, more than three weeks that had passed since, possibly the first couple of cases of the disease but nothing was, nothing had been done in the first three weeks. And of course there was already an outbreak. And of course, you probably could imagine that there’s this really huge shortage of medical responses [sic]. So that were [sic] the earlier failures, right.

JW: Yan, just to clarify something. I’m interested in what you just described, about the history that China went from doing nothing to total lockdown. And so I guess I’m just wondering, was there consideration of taking immediate steps first or what sort of prompted such a dramatic 180 in the government’s response to the crisis there?

YS: Yeah, that was [sic] great question. There were a couple of really sort of public housing officials or professionals and they went to Wuhan around, in mid-January, around the 20th, and they were trying to look into the issue and then they finally realized this is a serious disease, this is a serious virus. And they reported to the city of Wuhan as well as the National Council of China. They made it really clear that this could be very serious if nothing, sort of, would be carried out by them. So that definitely prompted the just sudden lockdown, even me, myself was surprised just to see the news come out on that day, you know, it’s a total lockdown on the 23rd. Yes. So definitely the professionals, the warnings from the professionals made a matter [sic], made it happen.

MA: And so Wuhan in China, they did not have the luxury of seeing the successes and the failures of what other cities and countries did to control the spread of the virus. Though I suppose we might even say in places with that luxury, the lessons were not necessarily heeded. What would you say that Wuhan and China, that they did especially well after this outbreak then and what did they do not so well?

YS: Mm hmm. Well, basically, everything began to change since February, right. I just mentioned that the city got locked down on the 23rd. But the last week in January, it was still a disaster because of course, there was a shortage of medical services when there were already many people that got sick, right. And then in February, basically beginning from the [sic] February 1, another important figure, I mean just important person, he’s the deputy director of the Ministry of Housing and Construction. Basically he suggested let’s do the paired assistance, right, there is a lack of medical services in Wuhan. And there’s a shortage of medical equipment, and the doctors and the nurses. Why don’t we just pair up the assistances. So basically, the country mobilized every other single province and the major cities, and each province and each major city, such as Shanghai or Beijing or Shenzhen, they assembled, all those cities assembled the best team of doctors, nurses, and with abundant PPE what they call personal protection equipment, and other medical equipment. So they all flew to Wuhan on basically, on February the 1 or 2 just during that couple of days. So basically from February the 1 to mid-February, it took them two weeks. At this time, you’re basically seeing dramatic change or dramatic improvement of medical resources through this pair assistant program, right. And after mid-February, things just basically smoothed down and the hospitals were able to be more responsive to all these patients, right. But at the same time, the things [sic] that also really worked well is the centralized quarantine. Still people, all the households weren’t allowed to go out the [sic] homes, not even for like walking or jogging. And each household basically obtained, I think, three vouchers per week. You could use the three vouchers to go outside the district, I mean, the housing like the housing project, the housing to go out to get groceries, or do some very essential sort of errands, but other than that, no more than three times.

JW: Well, and it’s been observed that the kinds of social limitations that the Chinese people were willing to accept, including rationing of times you can leave your house, are measures that might be just a much tougher sell, for example, in the United States.

YS: Absolutely. This is probably not a replicable mechanism just being adopted in other parts of the world. But it really worked well in China. So that’s why you probably can see a quick change in terms of the the curve, right. And you first see the flattening curve and then you see the declining curve of the occurrence of the cases.

NM: Yan, were the shelter-in-place [sic] enforced with digital tracking, or were there other mechanisms?

YS: Yeah, that’s a great question. So this is a really strict governance program, implemented by every smaller communities [sic], right. So essentially, every single communities [sic] implemented the gated program, right? So in the cities, no digital devices were implemented for that, but mostly just through a governing sort of mechanism there, through for example a homeowner association or through some other community level organizations. But then in the rural areas where you saw sort of, it’s really hard to have this physical limitation of entrance, right, and then that’s where the village leaders basically had a program flying the drones and they could detect people if they really move out and if they really aggregate and they didn’t really obey the social distance rule and then they could detect the incidents.

MA: So we have robots going up and down the causeway telling people to put on masks. We have drones flying around and, you know, sort of tracking people. I was reading in the New York Times this morning about what they’re doing in Seoul, South Korea, where everyone who gets tested for COVID, and maybe this is what we talk about when you talk about smart cities, is this what we mean when we talk about smart cities? Everyone who gets tested for COVID is required to install an app on their phone, which then tracks their movement and their whereabouts. But more than that, it lets other people see it, use the same app to see where once infected people are at that very moment. You know, so in the story, they gave the example you could be at a Starbucks, and all of a sudden your phone will ding, and your app will let you know that someone who has tested positive for COVID has just entered that Starbucks. Is this system in Seoul? Is this an example of what we’re talking about when we talk about smart cities? Or is this the type of technology that you think we can expect in the smart cities of the future?

YS: Sure, yeah. The Smart City meaning in plain language is definitely sort of an efficient way of using technology, right? Technology such as sensors, right, or video cameras or many other types of basically just sort of tracking devices to collect data. In this case, it’s sort of tracking where people move, right, and especially for the certain sort of sensitive cases, you could track where those people move and who were [sic] in contact with those people and sort of having a more effective way to you know, track people and have further sort of quarantine rules being set up following that. In many cities, in Seoul, in cities in Japan and also in China, the Smart City technologies have been used this time, in a very sort of pervasive way to deal with the disease. The AI, the artificial intelligence technology, has also been used to basically have temperature monitoring in all the public spaces in many other Chinese cities. In every single big transit station, they have AI sort of device [sic] installed to just monitor the temperature of each person moving in and out.

(musical interlude)

JW: This is “COVID Conversations”. I’m Jonathan Weiler here via Zoom with Matt Andrews, and our guests today are professors Yan Song and Noreen McDonald from the Department of City and Regional Planning at UNC.

(musical interlude)

JW: So, Noreen pivoting to just thinking about cities more generally, could you talk a little bit about how city planners think about health in cities, and how they try to manage the tremendous competing pressures of places where lots of people are going to live together? Just sort of talk more generally about what city planners have learned and what they think are sort of best practices for organizing social arrangements in urban areas?

NM: Well, I think the COVID-19 pandemic has been, I mean, it’s been so challenging for all of us, but those of us that think about cities a lot, it’s, you know, it’s really in the United States been about 100 years since we thought about planning our cities to deal with a pandemic and it brings us back to the very roots of the field. Planning emerged to deal with the ills of the industrial city, most of which were around health. You know, if you go way back, outbreaks of cholera, but certainly just really terrible living conditions that people were in, in overcrowded housing, so there was a lot of disease transmission, there was poor eating, low levels of education and planning emerges first focusing on water and sanitation to make sure that people have clean water. And then going on to think about how we have building codes so that we have factories that are safe, so that we have apartment buildings where people have access to light and water and bathrooms. And all the way on to zoning codes now which specify, you know, where residential, where homes should be, where businesses should be, where retail locations should be. And all of that emerged for the primary reason for [sic] protecting health, but we’ve really come away from that focus on health in some way. And now, we still talk about healthy cities, and healthy cities are a big interest but we’re focused on how do we make sure people have access to jobs, right, income is a central part of being healthy. How do people have access to parks? How do people have access to clean air? So we’re talking about it again, in terms of healthy cities, but I will say this pandemic brings us right back to the very roots of the field 100, 200 years ago.

JW: Noreen, just to follow up. Just thinking about, so about 10 years ago, I started reading The Power Broker by Robert Caro about Robert Moses. Ten years later, I think I’m about halfway through the book. But it is an incredible book and Robert Moses, the legendary planner of modern New York City. The thing that I think in some ways struck me the most, other than his kind of Machiavellian nature, was his absolute obsession with green spaces, public spaces, parks, his commitment at least in some ways, to ensuring that the poor, in particular, had places to go when they left their tenements, so that they could get fresh air, that they could take their kids to parks to play in. And so I’m just interested to hear just what you have to say about that kind of vision and how that’s sort of relevant to thinking about cities today.

NM: Yeah, I think on the required reading list for all planners is The Power Broker. I found the first 100 pages tough slogging but after that it went by fairly quickly. Robert Moses is fascinating because you look at the building of swimming pools in New York City, public housing projects, right, there are all, there is this emphasis, as you say on housing for the poor and amenities for the poor. But coupled with his desire to facilitate people getting away from the city, particularly the richer and more elite people on the parkways that he developed and on the parkways that went to places like Jones Beach at the Atlantic Ocean, which weren’t actually accessible to the poor people in the city who might not have cars. So, you know, I think he embodies the tensions in the field. These desires to address inequities, improve conditions, but also the fact that the elites often have better access. And people that can escape the city and have the means to do so benefited in particular from his road network and the parks that he created all along Suffolk County and Nassau County.

MA: Well and not to turn this into a, you know, dissertation about Moses, but when I think about him, I think about him in the terms of my baseball history course in which we talk about his refusal to give the Brooklyn Dodgers land. Because he wants a baseball stadium that people were going to drive to, exactly what you were just saying. He envisions transportation, when he thinks of transportation, he thinks about cars, he sees cars as the emblem of American modernism. I’ve seen these debates right now talking about cars versus public transportation. I’ve seen well, right-wing commentators, I think pushing the argument that COVID-19 means the death of public transportation, and I know that this is your field. But in the city, it seems impossible to transport everyone by themselves in a car, though maybe I’m making a mistake by framing this as a sort of car versus subway dichotomy. What do you see moving forward with regards to public transportation? I mean, we keep hearing these stories about how public transportation cars, subway cars, they were incubators of this virus. What’s the effect of this virus going to have on our public transportation system?

NM: I think it’ll have a big impact. I think we’re still assessing the impact that it has now. We know New York City transit workers have been struck down. Many have died at very high rates because of the exposures that they faced providing a really essential service, right. And not necessarily always compensated at that rate. The same thing in cities like Detroit, where you have a lot of workers who may not have access to a vehicle and are essential workers and still need to get there and buses still being full, and people facing exposure through that. So I think there’s two parts of it. There’s one, acknowledging the still critical work that these transit systems are doing, and they’re doing it right now, essentially, without any money because many of them are funded through sales taxes, which have gone way down. They’re also funded through fares, which have gone way down. So they’re facing big financial challenges plus the challenges to their staff. But if we start to look ahead and think about how this might come back, particularly as we sort of anticipate, maybe these rolling systems of cities opening up and then closing down a little bit, I think we will see people seek out alternative, less crowded ways of traveling. So what does that look like? In some places, it may look like more walking and biking, and you see cities experimenting with opening up streets, so that no cars are allowed on them and just people can get out and use them in a socially-distanced fashion. So you may not be able to build bike lanes more quickly right now, but you can limit where cars can go and give people better access that way. And that works for certain kinds of trips, you know, probably shorter to medium distance trips. I think cars also are, you know, they’re obviously a very socially-distanced form of travel and for people that do have access to cars, they will be a very attractive, continue to be a very attractive option. In our biggest cities, in places like New York, Boston, San Francisco, where there’s no way that all the workers can get to their offices in a private vehicle, even if they all had them, had one, that’s where we’re very challenged. What is the transportation system that can move people reasonably long distances? You know, going from Westchester into Midtown Manhattan or going from Eastern Long Island in, those are not trips that we’re gonna [sic] walk or bike. Those probably aren’t trips we can drive because there’s not enough road capacity. What does transit look like there? And that for me is the question that I’m still puzzling over. I think it looks like much more telecommuting, much more flexible work hours. We’re going to look to spread the peak in a different way. We used to talk in transportation about spreading the peak and we meant, not having everybody travel at 8am and 5:30pm and that same part, those same types of solutions will come into play.

JW: So and Yan, now on that score, could you maybe talk a little bit about how some Asian cities are navigating the issues that Noreen just mentioned? They have, I presume, very well developed public transportation systems. They’re crowded, they’re, some of them are now like Wuhan, opening back up after at least the first phase of this crisis. So can you talk a little bit about what public transportation and moving lots of people around, looks like in some of those places?

YS: So, we see some cities in Japan and Korea, basically, they maintained the public transit during the major outbreak of the virus. But then they sort of maintained the safety at the same time by very strict protective measures. For example, again asking people to wear protective devices and also asking for social distance on the cabin of the trains. And also, again very strictly monitoring and tracking the passengers’ movement, so that if anything happened, they could sort of track down where they should have more strict quarantine of potential or presumptive cases, right. So, those cities basically maintained a certain level of public transit. However, in Wuhan, as I just mentioned, the traffic, the public transit were [sic] suspended, right. And during this stage, but we still see a demand for people to moving [sic] around, especially by those people who are providing medical services, like nurses or doctors when they need to basically get off work in the middle of the night, for example, after their shifts. So in this case, a company called DiDi, and it’s the same version of Uber in the US, stepped in. They provided the shared vehicles for those people in need, especially not, you know, during regular hours where people could look for other transportation alternatives. But they sort of through this. This is also sort of a one approach of a smart city, right? You could sort of have the shared vehicle, in the shared economy so that you could provide flexible and sort of a demand on request services to people in need.

MA: I think this is a question for Yan and Noreen, just thinking about this in a big picture sort of way. Have you seen anything intrinsic to the design of certain cities that are allowing its residents to weather the storm better than other cities? Is there something about the way those cities were created, you know, that might serve as a model for cities moving forward learning to live with viruses, like COVID?

NM: This is Noreen. When I, when we first started talking about this, I think there was a lot of concern about density, and the idea that low density or rural areas will be protected. And I feel like this pandemic, in some ways, has shown us it’s not about density. We have cities that are very dense and have had terrible experiences. We have cities of similar density that, through their surveillance programs, whether it’s digital tracking, or human contact tracing, have been able to flatten the curve and really emerge much better. In fact, I think if we look in the paper now we’re seeing those rural areas get hit very hard, whether it’s through meatpacking plants or funerals that were super-spreading events, it’s become clear that none of us are magically protected because of where we live. And I think similarly, we’re not magically put at risk, you know, the transit systems, as we said, if that’s the only way that you can travel, that is a big risk. But even in cities, there’s usually alternatives available. But that’s what I’ve really been struck by. It’s about the way the governments responded and the public health programs they put in place, and not just about the size of the city or the density of the city.

YS: Yeah, this is Yan. I absolutely agree with Noreen. I also want to emphasize that the cities that have been doing well, really excelled in the mechanism of providing a great, sort of an efficient way of urban governance, right, through all this. For example, the pair assistant program that I mentioned in Wuhan or how the emergency responses [sic] reacted in many cities, and how different sectors in the government, also how different levels of government coordinate, I mean, all those made a difference in the way, again, flattening the curve. And that’s really what matters, the governing structure.

JW: You had both shared with us this, I guess, phrase in your field that density is not destiny. And it seems like what you’re explaining to us very clearly, is that there is no single blueprint for managing these competing pressures and tensions and resources and people. That it really, so much of it depends on good, thoughtful, holistic planning if we’re going to navigate a crisis like this and to allow cities to thrive, generally in an increasingly globalized, interconnected and therefore, vulnerable world.

NM: I think there are some themes that do emerge related to this governance idea, but we talk about it in terms of resilience, because a lot of what planning has been focused on is resilience to disasters, and that’s often been hurricanes, so something we’ve experienced a lot in North Carolina. But there it’s about having a city or a community where people have different ways to travel, or can telecommute because the community has invested in Wi-Fi or broadband access. So that there’s not only one way to do things, right. If you live in a community where the only way to get to work is driving, then if anything happens and the roads are not accessible, people aren’t going to be able to work. If there were bike lanes, if there were sidewalks, if there was transit, that might be more resilient. So I think it’s not about a specific design, but it is thinking about building systems that are redundant to failure, which at the very least increases your capacity, if any one of those goes out or if people need to lower the density in one of those systems.

MA: I have a question. I have a question for everyone. Jonathan, I’m gonna [sic] put you on the spot as well here. And maybe this is too starry-eyed of a question. But something I’ve been thinking about recently is, I’m trying to find the silver lining in all this right, and trying to think how we’re going to be better as a society moving forward. And I realize that ‘the good’ is a relative term, but I’m just wondering if some long term good can come from this crisis. You know, do you think that this crisis, and let’s think about people in cities, can foster in people a sense that the city is truly a shared space? You know, a space shared by old and young, and rich and poor, native born and immigrant. Is there any reason to think that, you know, we’re going to be stronger moving out of this moment, lead to a stronger sense of society as a collective whole? Or is this just going to be a trauma that we will be, you know, reeling from for decades?

NM: Well, we’ll all get out our silver balls here and look at them very closely.

MA: Well, that’s the thing right? As Jonathan knows, one of my my my favorite sayings is: I don’t make predictions, especially about the future. In some ways, I guess that’s what I’m asking people to do here. So maybe this question, we can scrap it. Or you know, maybe I’m asking you this question as human beings rather than as political scientists and as city planners.

JW: Yeah, I’ll start with a quick reflection. You know, I guess I’m of two minds about this. And, you know, thinking as a political scientist who’s thought a lot about political polarization, you know, there’s a negative view that this could make us even more polarized. The ways that certain parts of the country have experienced this very differently than other parts of the country, just for example, could exacerbate some of these long term antagonisms that have come to define our politics. On the other hand, it might be that we’re learning a lesson that there’s no hiding from each other. You know, that wherever you live, you are exposed and vulnerable to things like the possibility that a pandemic might strike your community. And I guess I do wonder whether, if that’s a lesson that gets sort of internalized, whether that might cause us to think a little bit differently about how we see each other, across different parts of the country, and different parts of the world.

YS: I could just speak for the early epicenter, the city of Wuhan. After this, people have been reflecting upon, you know, what can, what could we get out of this? And luckily, we’ve seen a stronger sense of community, right, the community being more inclusive, sort of inclusive in terms of the older, the elderly, right, the vulnerable. And sort of, how could we allocate community resources to reflect more the needs of the, sort of, the vulnerable, right. And also, we’ve seen a stronger sense of community just in terms of embracing and forgiving, you know, the polarized political debates during this difficult time, but then sort of trying to learn a lesson out from [sic] this.

NM: Yeah, I was gonna [sic] say for me, I feel like, people are experimenting every day trying new policies, whether it’s at the federal, state, or local levels, or international examples. And we’re throwing a lot of spaghetti at the wall, in our medical system, in our governance systems, I mean, we’re kind of trying universal basic income, sort of. We’re talking about making care for Coronavirus, potentially free. I mean, I don’t know how that will be implemented, right. But we’re implementing a lot of policies that, some could stick in the same way that we came out of the Great Depression with the programs for the New Deal. I don’t know how it felt at the time. We learned about those programs as if they were, sort of, a set of policies put in place already perfected, but maybe it wasn’t really that way at the time, maybe it was more ad hoc. And we’re certainly, we still have the legacy of that, of the institutions and the programs put in place, everything from the 30-year mortgage, right. The way most of us buy our homes emerged out of the tragedy of the Great Depression. So I’d like to think that some policies that help all sectors of society will stick with us.

JW: Thank you Noreen and Yan so much for joining us today and sharing your great expertise about cities and navigating the current crisis.

YS: My pleasure, thank you.

NM: Thank you.

JW: So this has been Episode Two of “COVID Conversations”. And we wanna [sic] thank the College of Arts and Sciences including Dean Terry Rhodes, and Senior Associate Dean Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld, whose brainchild this series was. This podcast is being produced by Matthew Belskie and Klaus Mayr and we could not possibly be doing this without them, so thank you so much. And we want to thank the communications office in the College of Arts & Sciences, especially Kristen Chavez and Geneva Collins for all the fantastic work they’ve done building our website which is covidconversations.unc.edu and getting the word out about the podcast. You can find us on SoundCloud, Spotify, Apple iTunes, the Google universe, and if you like us, please spread the word and rate us and share, and we look forward to seeing you next time.

Transcript edited by Kelsey Eaker.